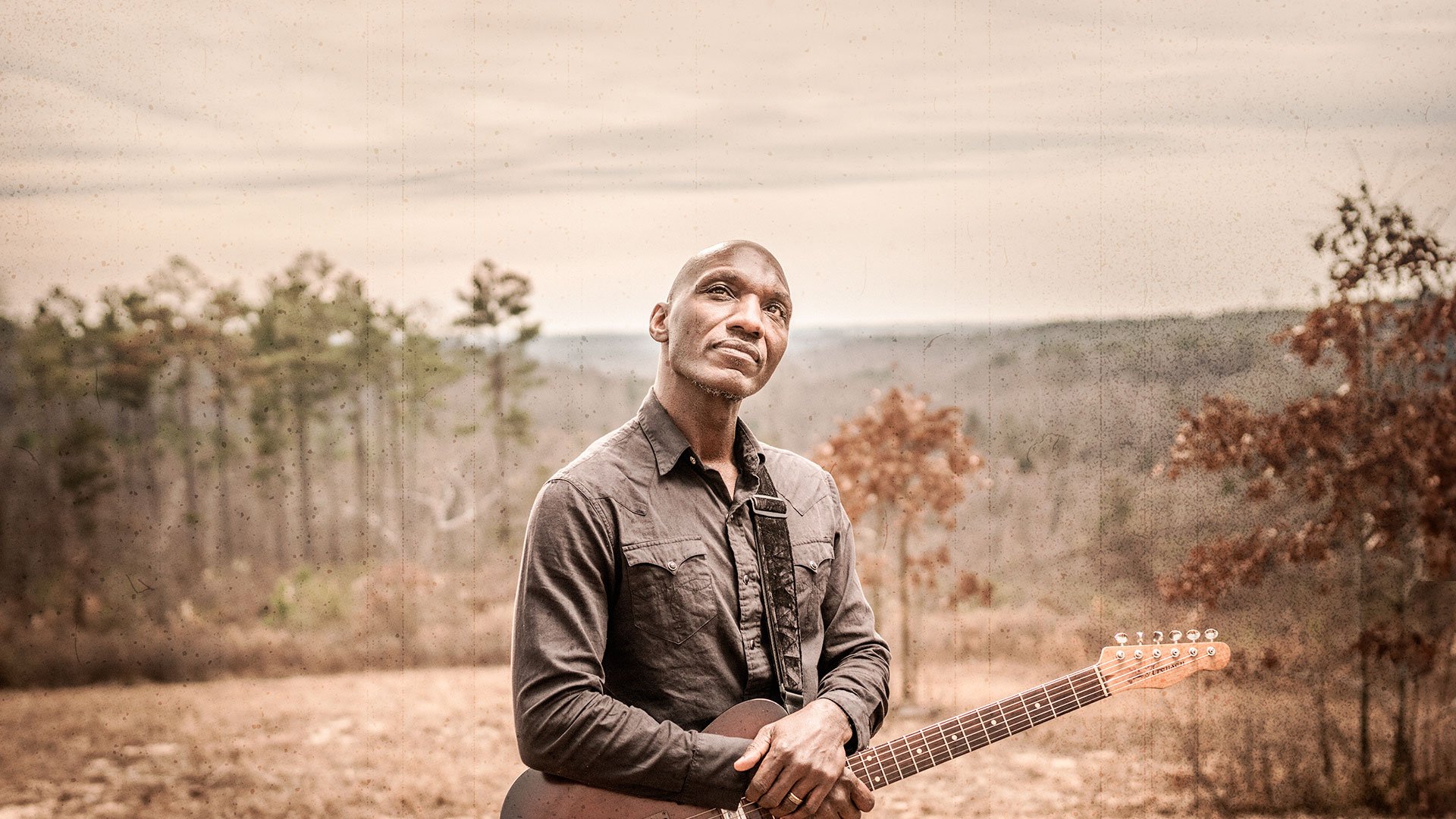

The official credit tells it like it is. “Recorded in an old building in Ripley, Mississippi” – that’s all the info we get, and all that we need.

When Cedric Burnside prepared to record Hill Country Love, the follow-up to his 2021 Grammy-winning album I Be Trying, he set up shop in a former legal office located in a row of structures in the seat of Tippah County, a town with 5,000 residents that’s known as the birthplace of the Hill Country Blues style.

“That building was actually going to be my juke joint. Everything was made out of wood, which made the sound resonate like a big wooden box,” said Burnside. He called up producer Luther Dickinson (co-founder of the acclaimed North Mississippi Allstars and the son of legendary Memphis producer/musician Jim Dickinson), who brought recording equipment into the empty space. “We recorded in the middle of a bunch of rubbish – wood everywhere and garbage cans,” Burnside says. “We just laid everything out the way and recorded the album right there.”

The 14 songs on the record were finished in two days, but in addition to being satisfied with the sound, Burnside believes that Hill Country Love represents real creative progress. “Every time I write an album, it's always different,” he says. “I'm always looking to express myself a little bit better than I did on the last one and talk about more things happen in my life. I think that every day that you’re able to open your eyes, life is gonna throw you something to write about and to talk about.

“So on this album,” he continues, “I'm a little bit more upfront and direct, because I went through some crazy feelings with family and with friends. Winning the Grammy was awesome, but people tend to treat you a little different when things like that happen.”

Certainly, plenty of things have happened in Cedric Burnside’s life since he went on the road at age 13, drumming for his grandfather, the pioneering bluesman R.L. Burnside. His two albums before I Be Trying – 2015’s Descendants of Hill Country and 2018’s Benton County Relic – were both nominated for Grammys. He has also appeared in several films, including Tempted and Big Bad Love (both released in 2001) and the 2006 hit Black Snake Moan, and he played the title character in 2021’s Texas Red.

Burnside is a recipient of a National Heritage Fellowship, the country’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts and was recently recognized with the 2024 Mississippi Governor's Art Award for Excellence in Music. He has performed and recorded with such diverse musicians as Jimmy Buffett, Bobby Rush, and Widespread Panic.

Yet as the title of the new album indicates, Burnside has never strayed far from the distinctive blues style introduced to the world by his “Big Daddy” R.L. and such other greats as Junior Kimbrough, Jessie Mae Hemphill, and Otha Turner. “I’ve been traveling my whole life, and the song ‘Hill Country Love’ gave me a chance to let people know that I love what I do and give a sense of how we do it in Mississippi – like, the house party is a tradition here, Big Daddy threw a lot of them. So that's what I was thinking about as I was writing that song – where I come from and also where I'm going, and how my journey has been to get to where I'm at now.”

Another song, “Juke Joint,” pays tribute to the local nightlife institutions that were central to Burnside’s growth both personally and musically. “The juke joint was a big part of my life,” he says. “I didn't go to church, the juke joint was my church, and the juke joint was my school. I was there all the time, from 10 years old until I was grown.”

At the same time, Burnside sees himself as an inheritor, not an imitator, of his native region’s blues style. “Big Daddy’s music, Junior’s music, Mister Otha’s music – my music is similar to theirs, but I'm a younger generation,” he says. “Whether we want to or not, we move on, and so my music will automatically sound a little more modern. But even if I tried to sound really modern, that old feel and old sound is just there. You might hear a song and think. ‘Wow, that sounds like it was recorded in 1959.’ I like that, but it's really just me growing up around it and falling in love with that sound.”

The album displays rock, R&B, and hip-hop elements, a range of sounds and emotions, from the self-explanatory instrumental “Get Funky” to the harsh truths of “Toll on your Life” and “Coming Real to You.” The most familiar composition is Burnside’s version of Mississippi Fred McDowell’s “You Gotta Move,” popularized by the Rolling Stones but often performed by Burnside’s grandfather at his Holly Springs farm. “He would get off the tractor and go sit on the porch and play for a couple hours, drink a little moonshine, and then go back to the tractor,” says Burnside, “and that's one of the songs that I always loved to hear him play.”

Many have drawn parallels between the polyrhythmic, droning sound of the Hill Country style, with its unpredictable chord progressions and bar counts, to West African music; that link is most obvious on the extended guitar introduction to “Love You Music.” But Burnside never really heard music from that part of the world until a few years ago, when a friend born in Gambia played him a record by Malian artist Ali Farka Toure. “I thought it was some old, underground Junior Kimbrough,” he says. “I was like, ‘Wow, man, I wonder do the Kimbrough family know about this?’ And then he started singing and my friend just started laughing!”

With “Closer,” Burnside strives for spiritual redemption; “I fall short on you, Lord, on some days/Please forgive me Lord, every day I pray,” he sings. “That song really resonates to me,” he says. “When I was writing it, I didn't just think about myself, I thought about everybody in the world, and getting closer to God. Every day you wake up, life is challenging, and it throws you all kinds of curveballs. Your faith is tested every day – that line is actually in the song, and I know people can relate to that as I can.”

To Cedric Burnside, Hill Country Love is a culmination of a career that’s already seen astonishing accomplishments and only keeps growing. What he wanted this time out was a real sense of honesty and integrity. “I compromised a little bit with my albums in the past,” he says, “and I didn't really have to compromise with this one, because I did it by myself. I paid for the engineer, paid for the musicians, I didn't have a record company there. We just went to play music, and how it came out was how it came out – and it came out great.

“I have to be true to where I'm coming from,” he continues. “On this album, the feeling that I had was like, I’m going to write what I feel, I’m going to write what's going on. Life gives you good and life gives you bad and you have to cope with it however you need to cope with it. My way of coping with things is through my music, so I thank the Lord for music. I really do.”